Ceramics blog

A Beginners Guide to Glazing Ceramics

Following up on my Beginners Guide to Underglazes, here’s a guide to glazes for beginner potters. I truly mean it when I say beginners because I’m in no way shape or form an expert on glaze chemistry, application or even mixing my own. What I’ll share here is my own experience with commercial glazes and underglazes and how they behave most of the time.

What’s a glaze ?

First things first, what is a glaze and why do we use glazes on pottery. Glazes are not mandatory, one can often cross paths with unglazed pottery and glazing your pieces will depend on mainly what you’d like to do.

Glazes are kind of a glassy varnish that covers tableware. Your industrially made mug in the cabinet is probably glazed. It gives pottery its shiny aspect. This shine comes with some interesting properties : it makes your ceramics vessel look cleaner and it also works as a liner. Unglazed pottery will often be more rough to the touch and therefore it will get dirt and all kinds of things in its asperities. That’s why it stains.

Commercial glazes vs. mixing your own glazes

Glaze formulas are nearly infinite, a potter can mix their own glazes or use commercial glazes. It’s often looked down upon but I use commercial glazes for many reasons. The first one is it’s easier to keep a bunch of glaze bottles than a great deal of buckets and containers. I like variety, commercial glazes allow me to test for as many options as I can afford without too much waste.

The downside of commercial glazes is that I’m dependent on a third party and manufacturers will change their recipes sometimes. A change in chemistry will often result in a variation in the final product. That’s how I ruined a batch of cool mugs recently. Although I was assured that the new clear glaze I used was compatible and mostly the same, it was definitely not !

So, as I mentioned in the beginner’s guide to underglazes, your way to go is testing more often than not.

How do glazes work ?

Glazes are applied on bisque fired pottery. Which means that ceramics pieces have been fired to a cone 06 to 04 – which is VERY DIFFERENT THAN CONE 4 to 6 ! Cones work from 022 to 01 and then from 1 to 14. A cone is a measurement of the heat work, not a precise temperature, but for simplification purposes, here’s a quick chart for indicative temperature at a 150 C / 270 F per hour heating rate in the last hour. It’s a bit complicated but it will give you a vague idea of what we’re dealing with here.

This chart also answers the questions : Can I bake pottery in my home oven ? No. Not even the luster would fire in a kitchen oven, sorry.

When a glaze is applied on bisqued pottery, it’s a powder mixed with water. When in contact with bisqued ceramics, the water is absorbed, leaving an even coat of powdered materials onto the pottery. Once in the kiln, it will heat up slowly until it reaches the desired cone, it’s 6 for most of us. This process melts the powder and it fuses with the clay, giving it a glassy look – because it’s mostly silica, which you also know as glass. This is super simplified, please don’t yell at me if you’re a chemist reading this 😀

During firing, glaze and ceramics also expand and contract with the heating and cooling of the kiln. This will cause most glaze issues if your clay body and glaze have different shrinkage ratios. More on that later.

| Cone | Temp (F) | Temp (C) | Firing Type | Color inside | Note |

| 10 | 2381 | 1305 | High Fire Glaze | White | Higher temp |

| 6 | 2269 | 1243 | Mid Fire Glaze | Yellow | |

| 1 | 2109 | 1154 | |||

| 04 | 1971 | 1077 | Bisque | Orange | |

| 06 | 1855 | 1013 | Bisque | Orange | |

| 020 | 1180 | 638 | Luster Fire | No change | Lower Temp |

Glaze application : Dipping, brushing, spraying

I never spray glazes so I won’t get into that. I just know that it requires equipment, a spray booth and PPE (respirator is a must have in the studio).

Brushing glazes

Brushing your glaze is the longest option for large vessels, there are a variety of brushes you an use. You’ll want to try and test your applications, documenting the number of layers and brush load. One important factor is to let coats dry completely before adding a new one, lest you’ll drag a bit of the bottom coat onto your brush. Brushing is nice for layering as you can control the amount of product used and count your layers.

Brush strokes might show, it all depends on your glaze and how forgiving it is. Test test test !

Dipping glazes

Dipping is the action of completely submersing your vessel into the glaze for a short amount of time. The time depends on your glaze’s water content. The more watery, the longer the dip. Glaze consistency is a whole topic in itself. I like to get my glaze to the consistency to the equivalent of coffee cream, and dip for a really short time, I usually just dunk the pieces and get them out immediately. This requires tongs most of the time as well as a damp sponge to get the tiny drips that will gather on the vessel’s lip.

A glazed item will need to have it’s bottom cleared of glaze in order to keep separate from the kiln shelf. During firing, all that is glazed will fuse with whatever is in contact : kiln shelf but also neighboring vessels if they touch. Since shrinking occurs during firing, we can safely place our pieces quite close together inside the kiln but they can never touch if glazed. Same for the kiln posts and walls.

Waxing for glaze resist

When dipping a batch of handmade pottery, I usually wax the bottoms. This means I’m adding a resist – like drawing gum or something resembling bee’s wax. The wax will not let any glaze adhere where it’s applied. It will burn off in the kiln.

Important tip for all of you beginner glazers who use wax : Waxing doesn’t mean you do not have to clean off excess glaze from the bottom. There is always a little spot of glaze ON the waxed part and it will mess up both your shelf and your piece when the wax burns and the glaze melts” I’ve witnessed this time and again at the studio with newer members. So WAX + SPONGE, always.

Glazing figurines and pendants

Figurines and pendants are also dipped, but in a smaller bucket. I wax and sponge the bottoms of my figurines. Sometimes I simply clean with a sponge and forget about wax, especially if I’m working on a small batch.

Pendants, on the other hand, are entirely glazed. I suspend them in the kiln so that nothing touches them.

Clear glazes and underglaze interaction

My work mainly consists of underglaze illustration covered with a clear glaze for white vessels, porcelain jewelry and figurines. I’m relying on commercial glazes and recently, many changes occurred : from mine closing to soaring material prices. As a result, manufacturers changed formulas and recipes. Which had consequences on my work.

Underglaze usually doesn’t like clears with zinc. Zinc will make a glaze move and smudge underglazes, especially blacks. It will also mess with pinks and reds. I usually worked with Tucker’s 602T, Amaco’s Velvet underglazes and PSH 909 Porcelain or Plainsman M370 white stoneware. Recently though, because of some formula changes – which brands will not always communicate – I had a few issues with crazing. I changed my clay to Tucker’s Bright white which worked well with their 602T Clear and Amaco’s underglazes. But then the 602T glaze was completely discontinued. Which started me on a quest for a better clear.

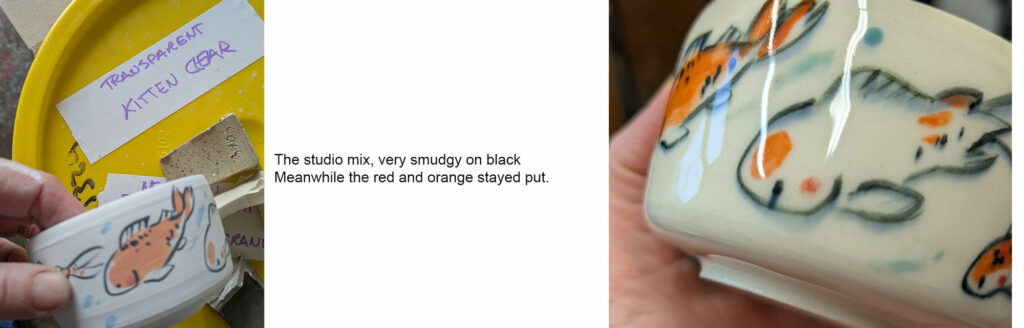

I tested several brands and the studio mix called Kitten Clear. One clear winner is Amaco’s HF9 which is zinc free. My next step is to formulate my own clear !

I hope this was helpful for you if you’re new to glazing pottery. I will of course add to this piece along the way. If you have questions, feel free to send them via the contact form !